There are duwendes in the streets of Iloilo: A tale of (re)becoming

- Erich Marie Mendoza

- 1 day ago

- 3 min read

There is a mound of untouched soil in our backyard where beliefs are embedded. I have learned of the whimsical stories about its unseen, mischievous owner, but it was my mother’s tales that shaped my childlike wonder and belief in this intangible creature—the one they called a duwende. We offer our respect to the land and its owner, and the duwende blesses us in return with protection, wisdom, and riches that transcend materiality. I have never seen its face, but the duwende always visited in my dreams, alluding to the chances I can carve for myself. It manifested in my passions and aspirations, and it was my belief in this creature that allowed that piece of land to withstand different faces of disaster.

Belief carries an immense power to those who wield it, but it does not mean that it is constantly unwavering. We are often confronted with the idea of the real world, where reality is defined by homogeneity. But when the land is eroded, and the intangible becomes materialistic, where does the duwende go? Does it die? Does it confide in wrath and vengeance? Does it weep and yearn for the place it once owned? Or does it continue to guard the debris of what has remained after the destruction, patiently waiting for you to come home?

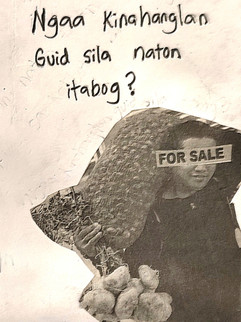

Artists of Kikik Kollektive have ventured into the sensibilities of their inner duwende through a gathering and zine-making last February 1, where an intuitive space was created for remembering, rediscovering, and perhaps, (re)becoming. The workshop for zine-making was led by Lady Kyla and Mary Louise, who were generous enough to share their expertise. The rawness and vulnerability emanating from each individual have sustained the flow of introspection permeating the venue. We carried and remembered different stories— different duwendes, but what our zines strikingly have in common is the presence of our land, of our nature, of our iloy-duta. It weaves the fabric of our belief systems as Filipinos and our spiritual connection with nature amidst this time of global homogeneity. In the transpersonal Filipino worldview (Bulatao, 1992), our consciousness is not isolated within the body, within the boundaries of an individual, but is interconnected and a part of the larger world. It embraces our pre-colonial indigenous belief with our land and its inhabiting entities in the form of spirits. The essence of deep ecology (Naess) highlights the inherent importance of nature, how are interconnected and a part of it. This resonates with our transpersonal worldview, with the intricate threads linking us as human beings, our tangible world, and the intangible entities that reside within.

The gathering created a door for us to come home. To pay our respects to the land and to our elders. To relearn our “Tabi-tabi po”. And most importantly, to relocate and give autonomy to our duwende. We often find ourselves caught up with the standardized values established in this materialistic and consumeristic world that we find it difficult to make sense of who we are, of our duwende, of the fragments that make us whole.

When our belief in the land is lost and is reigned over by dominating structures, where does our duwende go?

Perhaps, it seethes in vengeance. Perhaps, it weeps in sorrow. But what is vengeance if not frustrations masked in anger for the interests you have abandoned? What is sorrow if not grief for the passions you have sacrificed? Among its many known qualities, a duwende is an enduring immortal. It endures time. It endures sacrifices. It defies death, mortality. It remains in its territory, protecting this inkling ember, just patiently waiting for you to seek your way home again.

The sharing of stories encapsulated in our zines concluded around dusk, a period believed to be the time of entities such as duwendes. We bid farewell to each other and rode our way home to different areas of Iloilo.

I can only hope that the people wandering the streets of the city or those riding the jeepneys have said their “Tabi-tabi po.” They may have encountered a duwende or two.

Comments